were charitable organisations dedicated to the free education of destitute children in 19th-century Britain. The schools were developed in working-class districts and intended for society’s most impoverished youngsters who, it was argued, were often excluded from Sunday School education because of their unkempt appearance and often challenging behaviour. After a few such schools were set up in the early 19th century by individual reformers, the London Ragged School Union was established in April 1844 to combine resources in the city, providing free education, food, clothing, lodging, and other home missionary services for poor children. Although the Union did not extend beyond London, its publications and pamphlets helped spread ragged school ideals across the country before they were phased out by the final decades of the 19th century.

Working in the poorest districts, teachers (often local working people) initially utilised stables, lofts, and railway arches for their classes. The majority were voluntary teachers, although a small number were employed. There was an emphasis on reading, writing, arithmetic, and study of the Bible, and the curriculum expanded into industrial and commercial subjects in many schools. It is estimated that between 1844 and 1881, about 300,000 children went through just the ragged schools in London alone.

The Ragged School Museum in the East End of London, housed in buildings previously occupied by Thomas John Barnardo, shows how a ragged school would have looked. It provides an idea of the working of a ragged school, although Thomas Barnardo’s institution differed considerably in practice and philosophy from the schools accountable to the London Ragged School Union.

Several schools claim to have pioneered truly free education for impoverished children. They began from the late 18th century onwards but were initially few and far between, only being set up where someone was concerned enough to want to help local disadvantaged children towards a better life,

In the late 18th century, Thomas Cranfield offered free education for poor children in London. Although a tailor by trade, his educational background had included studies at a Sunday school on Kingsland Road, Hackney and in 1798, he established a free children’s day school on Kent Street near London Bridge. By his death in 1838, he had established 19 free schools offering opportunities and services daily, nightly, and Sundays for children and infants living in the lower-income areas of London.

John Pounds, a Portsmouth shoemaker, also provided significant inspiration for the movement. When he was 12, his father arranged for him to be apprenticed as a shipwright. Three years later, he fell into a dry dock and was crippled for life after damaging his thigh. Unable to continue as a shipwright, he became a shoemaker and, by 1803, had a shop on St Mary Street, Portsmouth. In 1818, Pounds, known as “the crippled cobbler”, began teaching poor children without charging fees. He actively recruited them to his school, spending time on the streets and quays of Portsmouth, making contact, and even bribing them to attend with the offer of baked potatoes. He taught them reading, writing, and arithmetic, and his reputation as a teacher grew; he soon had more than 40 students attending his lessons. He also gave classes in cooking, carpentry, and shoemaking. Pounds, who died in 1839, quickly became a figurehead for the later ragged schools movement, his ethos being used as an inspiration.

In 1840, Sheriff William Watson established an industrial school in Aberdeen, Scotland to educate, train and feed the vagrant boys of the town. In contrast to the earlier efforts of Pounds and Cranfield, however, Watson used compulsion to increase attendance. Frustrated by the number of youngsters who committed petty crimes and faced him in court, he used his position as a law official to arrest vagrant boys and enrol them in the school rather than send them to prison. His Industrial Feeding School opened to provide reading, writing, and arithmetic, as Watson believed that gaining these skills would help them rise above the lowest level of society. It was not confined to the ‘three R’s’, however, as the scholars also received instruction on geology. Three meals a day were provided, and they were taught valuable trades such as shoemaking and printing. A school for girls followed in 1843, and a mixed school in 1845, and from there, the movement spread to Dundee and other parts of Scotland.

On Sunday, 7 November 1841, the Field Lane ragged school began in Clerkenwell, London., and it was the secretary of the school, S. R. Starey, who first applied the term ‘ragged’ to the institutions in an advert he submitted to The Times seeking public support. Historians have debated how connected the movement was between England and Scotland. E.A.G. Clark argued that ‘the London and Scottish schools had little in common except their name’ More recently, Laura Mair has demonstrated that literature, philosophy, and passionate individuals were shared between schools. She writes that ‘schools forged significant links across cities and countries that disregarded physical distance

In Edinburgh, the first example was the Vennel Ragged School (aka New Greyfriars School) created by Rev William Robertson, the minister of the nearby New Greyfriars Church, in 1846 on the ground on the north-west corner of George Heriot’s School. The unassuming Robertson was, however, eclipsed by the self-promoting Rev Thomas Guthrie, who created a parallel Ragged School on Mound Place, off Castlehill in April 1847. Guthrie placed himself at the forefront of the movement in Scotland but was certainly not alone in his aims. His ‘Plea for Ragged Schools’, published in March 1847 to garner the public’s support for a school in the city, laid out his indisputable arguments that proved highly influential. Guthrie was first introduced to ragged schools in 1841 while acting as the Parish Minister of St. John’s Church in Edinburgh. On a visit to Anstruther in Fife, he saw a picture of John Pounds in Portsmouth and felt inspired and humbled by the cobbler’s work.

In 1840, the London City Mission used the term “ragged” in its Annual Report to describe its establishment of five schools for 570 children. The report stated that the schools had been formed exclusively for children “raggedly clothed”, meaning children in worn-out clothes who rarely had shoes and did not own sufficient clothing suitable to attend any other school. By 1844, there were at least 20 free schools for the poor, maintained through the generosity of community philanthropists, the volunteers working with their local churches, and the organisational support of the London City Mission. During this time, it was suggested that it would be beneficial to establish an official organisation or society to share resources and promote their common cause.

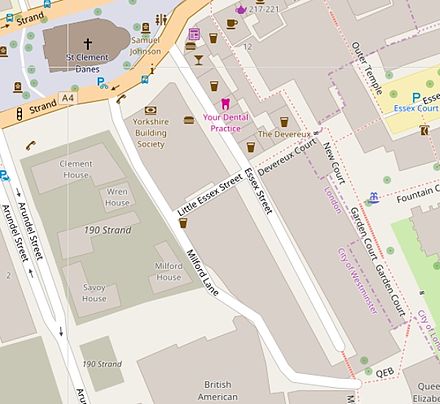

Then, in April 1844, the London Ragged School Union was founded during a meeting of four men to pray for the city’s poor children. Starey, the secretary of Field Lane school, was present along with Locke, Moutlon, and Morrison, and they formed a steering committee to address the social welfare needs of the community. On 11 April 1844, at 17 Ampton Street off London’s Grays Inn Road, they facilitated a public meeting to determine local interest, research feasibility, and establish structure. This was the birth of the London Ragged School Union. Mr Locke called for more help in keeping the schools open. Many petitions for funding and grants were made to Parliament to assist with educational reform. He asked the government to give more thought to preventing crime, rather than punishing the wrongdoers and said the latter course only made the young criminals worse. Several people volunteered and offered their time, skills, and talents as educators and administrators of the ragged schools. These included significant social reformers whose broad ranging concerns included education, animal welfare, public health and In 1844, Lord Shaftesbury became the London Ragged School Union president. He used his knowledge of the schools and refuges and his understanding of low-income families’ living conditions to pursue legislation changes. He served as the president for 39 years, and in 1944 the Union adopted the name “Shaftesbury Society” in his honour until, in 2007, the Society was merged with John Grooms, taking the new charity name of Livability. Shaftesbury maintained his commitment to the Ragged Schools and educational reform until he died in 1885.

In 1844, Lord Shaftesbury became the London Ragged School Union president. He used his knowledge of the schools and refuges and his understanding of low-income families’ living conditions to pursue legislation changes. He served as the president for 39 years, and in 1944 the Union adopted the name “Shaftesbury Society” in his honour until, in 2007, the Society was merged with John Grooms, taking the new charity name of Livability. Shaftesbury maintained his commitment to the Ragged Schools and educational reform until he died in 1885.

In 1843, Charles Dickens began his association with the schools and visited the Field Lane, (now Farringdon Road), Ragged School. He was appalled by the conditions yet moved toward reform. The experience inspired him to write A Christmas Carol. While he initially intended to write a pamphlet on the plight of poor children, he realised that a dramatic story would have more impact.

Dickens continued to support the schools, donating funds on various occasions. He donated funds along with a water trough at one point, stating it was “so the boys may wash and for a supervisor”! (from a letter to Field Lane). He later wrote about the school and his experience in Household Words. In 1837, he used the street called Field Lane as a setting for Fagin’s den in his classic novel Oliver Twist. Charles Spurgeon and the Metropolitan Tabernacle were also supporters. In May 1875’s Sword and Trowel Spurgeon recorded:

A most interesting and enthusiastic meeting was held in the Lecture Hall of the Metropolitan Tabernacle on Wednesday, the 17th ult., in connection with Richmond Street Ragged and Sunday Schools. After tea, at which about six hundred persons sat down, Mr. Olney took the Chair, and the public meeting was addressed by Dr. Barnardo, J. M. Murphy, and W. Alderson, Mr. Curtis, of the Ragged School Union, and the superintendents, Messrs. Burr and Northcroft. Mr. J. T. Dunn gave a brief sketch of the rise and progress of this good work. The friends heartily responded to an earnest appeal for help to build new schools, and contributed £128 17s. ld. It is proposed to raise another £100 by 23rd of June. The friends have thus raised in a few months over £350, which, with Mr. Spurgeon’s promise of £150, makes £500. At least £300 more is required.

There was a massive growth in the number of schools, teachers, and students. By 1851, the number of educators would grow to around 1,600 persons. By 1867, some 226 Sunday Ragged Schools, 204 day schools, and 207 evening schools provided a free education for about 26,000 students. However, the schools relied heavily on volunteers and continually faced problems finding and keeping staff. Women played an important role as volunteer teachers. A newspaper report on the progress of the schools announced that ‘the most valuable teachers in ragged schools are those of the female sex’.

The ragged school movement became respectable, even fashionable, attracting the attention of many wealthy philanthropists. Wealthy individuals such as Angela Burdett-Coutts gave large sums of money to the London Ragged School Union. This helped to establish 350 ragged schools by the time the Elementary Education Act 1870 (33 & 34 Vict. c. 75) was passed. As Eager (1953) explains, “Shaftesbury not only threw into the movement his great and growing influence; he gave what had been a Nonconformist undertaking, the cachet of his Tory churchmanship – an important factor at a time when even broad-minded (Anglican) churchmen thought that Nonconformists should be fairly credited with good intentions, but that cooperation (with them) was undesirable”.The ragged schools’ success definitively demonstrated a demand for education among people experiencing poverty. In response, England and Wales established school boards to administer elementary schools. However, education was still not free of fees. After 1870, public funding began to be provided for elementary education among working people.

School boards were public bodies created in boroughs and parishes under the Elementary Education Act 1870 following campaigning by George Dixon, Joseph Chamberlain, and the National Education League for elementary education that was free from Anglican doctrine. Board members were directly elected, not appointed by borough councils or parishes. The demand for ragged schools declined as the school boards were built and funded. The school boards continued in operation for 32 years. They were officially abolished by the Education Act 1902, which replaced them with local education authorities.

Founded in 1990, a Ragged School Museum occupies a group of three canalside buildings on Copperfield Road in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets that once housed the largest ragged school in London; the buildings had previously been used by Dr Thomas Barnardo.

Barnardo arrived in London in 1866, planning to train as a doctor and become a missionary in China. In London, he was confronted by a city where disease was rife, poverty and overcrowding endemic, and educational opportunities for the poor nonexistent. He watched helplessly as a cholera epidemic swept through the East End, leaving more than 3,000 Londoners dead and many destitute. He gave up his medical training to pursue his local missionary works and, in 1867, opened his first ragged school where children could gain a free primary education. Ten years later, Barnardo’s Copperfield Road School opened its doors to children, and for the next thirty-one years, it educated tens of thousands of children. It closed in 1908, by which time enough government schools had opened in the area to serve the needs of local families.

The buildings, originally warehouses for goods transported along the Regent’s Canal, then went through various industrial uses until, in the early 1980s, they were threatened with demolition. A group of local people joined together to save them and reclaim their unique heritage. The Ragged School Museum Trust was set up and opened a museum in 1990.

The museum was founded to make the history of the ragged schools and the broader social history of the East End accessible to all. An authentic Victorian classroom has been set up within the original buildings, in which 14,000 children each year experience a school lesson as it would have been taught more than 100 years ago.

SDW

Sources:- Wikipedia, Ragged University.